You might think that virtual reality (VR) is a relatively new phenomenon, sparked by the success of the Oculus Rift. But actually, VR has been around in some form or another since the early 1960s. Since research into VR has always been decades ahead of general release, unfortunately a lot of its history has fallen to the wayside. We’ll explore these fascinating advances in technology, starting with VR’s inception in the 1960s. We’ll look at the many strides forward in the 70s and 80s, like the mother of Google Maps. We’ll even discuss what’s best forgotten; the VR gaffes in the 90s that almost killed public appetite for the technology! Then, we’ll look to the state of VR today, and examine public response. Lastly, we’ll look to the future, and consider how VR will grow; at home, and in the workplace. This is a truly exciting time for VR, with promising new technology right around the corner.

Now, with all that being said - what is virtual reality, exactly? Technically, VR completely substitutes reality with an interactive, and immersive computer simulation, often with the help of equipment like HMDs (head-mounted displays), or wired gloves (that respond to hand movement). Other forms of entertainment, like films, could be considered immersive. However, the film will not respond to you in any way. If you turn your head, the illusion is shattered. But with VR, the environment will respond to your actions.

It’s easy to confuse VR with her sisters - artificial reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR). Often there’s overlap between the three. For simplicity’s sake, I will largely use ‘VR’ throughout.

AR doesn’t completely substitute reality. Often, AR uses a device’s camera as a ‘window.’ As you look through, you’ll find more information overlaid on top. For example, AR is common in pro cycling. Many cyclists use smart glasses that let them keep a constant eye on the road, and their stats.

On the other hand, MR puts simulated objects into the real world. Projector-based VR is the most frequent example, and is often found in showrooms, and art galleries. Participants see the virtual installation by wearing 3D glasses, or HMDs.

VR in the early 20th century

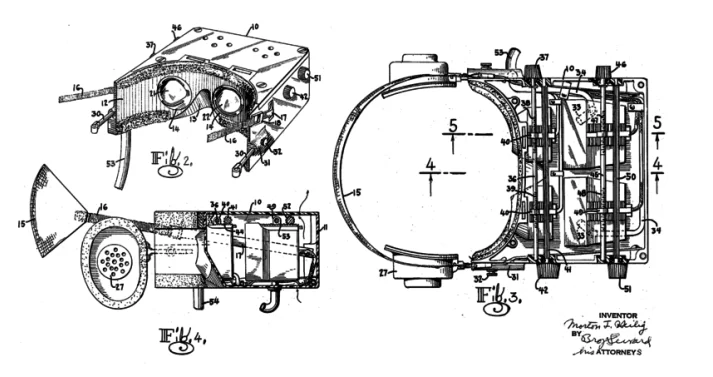

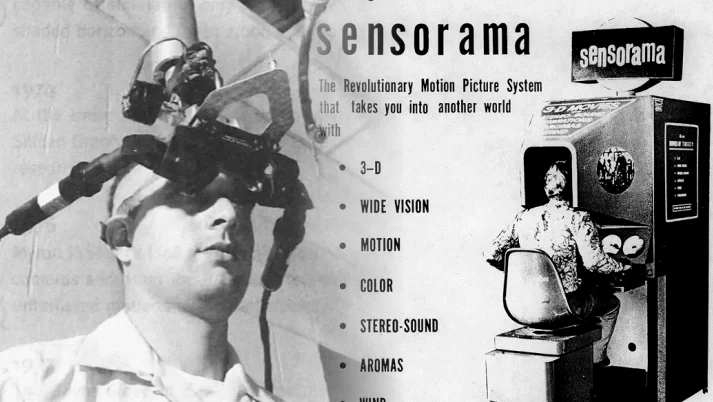

Morton Heilig was an American inventor, and pioneer of VR cinema. His first great invention was the Sensorama, patented in 1962. The Sensorama was an individual 4D cinema, featuring five films shot, produced, and edited by the man himself. Amongst these were “Motorcycle” and more curiously, “I’m a Coca Cola Bottle.” The Sensorama used sight, sound, smell, and touch to enhance its films. In “Motorcycle,” the chair would vibrate, and there were even handlebars you could hold onto, shaking to simulate a real ride. To add to the illusion, a strong breeze, and scents were released from the Sensorama’s vents. Unfortunately, due to the prohibitive cost of film-making, the Sensorama never progressed beyond prototyping. But Heilig wasn’t deterred. In 1969, he unveiled his plans for a full-size 4D cinema. The Experience Theatre would have had - in addition to all the Sensorama’s features - temperature variations, and tilting seats, much like 4D cinemas today. Disney originally expressed interest, but this invention was also never put into production.

In the Sensorama, we can see a recurring theme in VR. Leaps forward were hindered by a lack of consumer, and investor interest. 4D cinema would only re-emerge decades later.

In 1961, the Philco Corporation developed the Headsight, one of the first HMDs. Beneath its bulky exterior, it had head-tracking, and a video screen for each eye. It connected to a remote closed-circuit camera, and was initially developed for the US military to scout dangerous territory.

Seven years later, Harvard professor Ivan Sutherland built upon these groundbreaking developments with his own HMD. The aptly named Sword of Damocles was so heavy, it had to be suspended from the ceiling! His true breakthrough was realising that HMDs didn’t need to be connected to a camera, but instead could be connected to a computer. Reflecting on his invention in 2018, Sutherland recalled that “that replacement allowed us to view a mathematical world of our own choosing.” For the first time, users of the Sword were able to see into a virtual world. Although they could only see wireframe rooms, this marked a huge leap forward in VR.

VR in the 70s and 80s

These decades saw more widespread interest in VR. HMDs were refined, the first virtual, navigable worlds were created, and the world’s first commercially available VR was released.

In the late 1970s, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab’s artist-in-residence David Em created the first navigable virtual world. In 1978, MIT undergrad Peter Clay, with help from Bob Mohl, and Michael Naimark, expanded on this idea. Instead of creating an art project, they developed a virtual version of Aspen, Colorado. Their virtual city could be visited in three modes; summer, winter, and a 3D polygonal model of the entire city. To gather the footage needed for this project, they drove through Aspen with four 16mm film cameras. These were programmed to take a still shot every 10 feet. Then, they used a database to transpose their images onto a 2D street plan of the city. Users could ‘walk’ around the city in any direction. Here, you can see the seeds of Google Map’s Streetview, that would be released almost 30 years later.

At the same time, we also saw vital development of VR headsets. Eric Howlett, an American optic designer, invented an incredibly wide angle stereoscopic camera lens. It was dubbed the Large Expanse Extra Perspective (LEEP). Although it was initially used in cameras, NASA engineer Michael McGreevy, heard about the technology and realised that they could be used in NASA’s development of their own HMD, the Virtual Environment Display System (VEDS). Thus, NASA became one of Howlett’s largest clients.

Thanks to the availability of small, affordable LCD televisions, better computer graphics, and the LEEP lens, they were able to use their VEDS to develop research into telerobotics, data management, and human factors research. The LEEP lens was so wide-angle, it almost perfectly matched human peripheral and binocular vision. NASA released a video explaining this lens contributed to a “sense of presence in the...synthesised environments” that the VEDS displayed. And better yet, it didn’t require suspending from the ceiling!

Nasa didn’t just pioneer lighter-weight VR headsets - it also featured some of the first motion-tracking hand controls. The user could wear two wired gloves, that recorded arm, hand, and finger movement, allowing them to interact with virtual objects. Its other controls were speech recognition, and a 3D cursor - a small black, handheld puck that could select objects in the virtual space.

However, NASA wasn’t the only one developing wired gloves at the time. Jaron Lanier founded VPL Research, which would develop the Dataglove. In 1989, it was sold to Nintendo, and became known to the world as the infamous Power Glove, a controller allegedly compatible with the NES. VR had finally made its way into the home. Unfortunately, its poor controls (delicately described by some as “imprecise”) made it crash and burn soon after its release. Due to its poor reception, more planned games using the Power Glove were immediately scrapped, and its poor design is still mocked today.

And remember Morton Heilig’s Sensorama? Over two decades later, 4D cinema finally got investor backing. In 1982, the world’s first commercial 4D film was released. “The Sensorium” was screened in Baltimore’s Six Flags. Like the Sensorama, it even included scents! To this day, 4D cinemas tend to be found in theme parks.

VR in the 90s

The early 1990s saw a boom in the development of VR for entertainment. Eager to capitalise on Nintendo’s failure to dominate the market, large companies like Sega started developing their own technology.

In 1991, Sega announced the development of its own VR headset, intended for use with home consoles. It was developed in conjunction with four games, including a port from one of their arcade games. However, user testing revealed that it caused extreme motion sickness, and headaches.

In an attempt to recoup their losses, Sega re-packaged the technology from the headset for their VR-1 arcade attraction in 1994. Although it was prominently featured in SegaWorld amusement arcades, critics noted that its graphics were worse than their other arcade games. It was eventually dismissed as a gimmick.

To save face, Nintendo hit back with its own VR headset in 1995. The Virtual Boy was released blatantly unfinished, in order to focus on the Nintendo 64. Like the Power Glove, it was hugely underwhelming, and caused the same health concerns as Sega’s headset.

While these two corporations were floundering in this new field, a dark horse emerged from the pack. In 1991, Virtuality was released. It was the world’s first mass-produced, networked, multiplayer VR system. There were two versions of its ‘pods.’ One allowed people to play standing up, with motion trackers that responded to a handheld joystick - similar to the later Wiimote. The other allowed for seated play, with different controls depending on the game. Players could cling to joysticks, steering wheels, or even aircraft yokes. Each pod cost an eye-watering $73,000, but the price didn’t put buyers off. Although its pods suffered from low resolution, and lack of software support, Virtuality shocked industry experts. In 1992 Computer Gaming World hailed it as the frontrunner of “fully immersive systems.”

In 1995, Virtuality released one of the first applications for VR in the workplace. Project Elysium was developed for architecture, and construction companies. The technology allowed builders, and clients to visualise finished projects in greater detail than blueprints allowed. For many years, this use of VR was one of the most prominent in the workplace.

Projection-based VR also made its first strides in the 1990s. In 1991, Carolina Cruz-Neira developed the Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) as part of her PhD thesis. In these ‘VR rooms,’ a high-resolution display is projected onto walls covered in projection screens. While inside the room, users wear 3D glasses that let them see objects hanging above the ground. Their movements are tracked by sensors on their glasses, and the projection adjusts accordingly to maintain the illusion.

The world’s first interactive virtual reality film was created in 1992 by Nicole Stenger, a research fellow at MIT. She developed a short film that viewers could interact with, by wearing a VPL Dataglove, and high-resolution goggles.

Military uses of VR were also being explored. In 1991, Louis Rosenberg, at the time a Stanford undergrad, was the first to prove that overlaying virtual information over the real world significantly enhanced performance. He was snapped up by the U.S. Air Force, and developed their Virtual Fixtures system the very next year.

Virtual Fixtures had a very unique design. The user wore a bulky upper-body exoskeleton, as well as a headset. The user’s movements in the exoskeleton controlled two physical robot arms, and the headset gave the impression that the user’s arms had been replaced by the robots. The headset displayed virtual overlays that were intended to help the user while performing real tasks.

VR in the 2000s

After the VR boom of the 1990s, there was little development in this field.

In 2001, Z-A Production developed a PC-based version of CAVE. Its compatibility with average PCs made CAVEs cheaper, and more accessible. As a result, CAVEs have remained popular in universities, as well as engineering and construction companies.

As mentioned earlier, Google introduced Street View in Google Maps in 2007 - arguably the direct descendent of the Aspen Map developed almost 30 years prior!

VR in the 2010s

After a decade of near-complete disinterest in the potential of VR, the 2010s saw an explosion in development, arguably thanks to the success of the Oculus Rift.

In 2010, Palmer Luckey designed the first Oculus Rift prototype. Although its lens suffered from distortion, it boasted a wider field of vision than that currently on the market. However, the lens suffered from distortion. The Rift was presented at E3 in 2012, and launched their Kickstarter the same year. Just four months later, they had blown past their original funding goal of $250,000, and had raised $2.4 million. In 2014, Facebook bought the technology for a whopping $3 billion. The Rift went through several more prototypes before officially shipping to consumers in 2015. The lens distortion had been fixed, the displays were higher resolution, and there was integrated audio. Accessories included the Oculus Touch (two handheld controllers) and the Constellation sensor. These sensors let players experience room-scale VR at home for the first time. In early summer 2019, they released the next-gen Oculus Rift S, which has integrated room-scale VR.

While all this was going on, several other companies were rapidly developing their own VR products. For example, in 2014, Sony launched Project Morpheus, a headset compatible with the PS4. Valve Corporation, and HTC released their own VR headset, with their own version of the Constellation in 2016.

Looking Forward

After decades of VR’s confinement in research labs, there’s finally a real hunger for the technology. By 2016, at least 230 companies had joined the fray. Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google, are a few of the many major companies that now have dedicated VR development teams.

No longer a feeble arcade gimmick, VR has successfully penetrated the home-console market. Several games have successfully taken full advantage of the ultimate first-person perspective, like Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes. In this game, the wearer of the Oculus Rift attempts to defuse a fiendishly complicated bomb, while getting advice from other players reading from a complicated manual.

But if there aren’t more improvements in the technology, can we expect another slump in consumer interest, as we did in the 2000s?

The sheer power of widespread industry backing makes this unlikely. As previously discussed, Facebook alone has invested billions into developing new products. Unlike in the 1990s, it isn’t just a struggle between a couple companies. The largest names in technology are putting their best and brightest towards innovating in this exciting field.

So where can we expect improvements to be made?

Although VR has come far, there are still many potential ways to increase immersiveness. Haptic interfaces, that simulate the feeling of touch, are still very undeveloped for VR. VR headsets often still require handheld remotes, and displays need higher resolutions, and framerates, to appear more realistic. There is also development into making room-scale VR safer. The next-generation Oculus headsets, such as the Rift, Rift S and the Quest, uses new software that claims to warn players of obstacles, and it’ll be interesting to see how this holds up.

As with any new technology, there has been some public concern about its impact.

In 2017, Wiggin LLP surveyed over 2000 British adults on their attitude towards ethics and VR. Although only 16% of those surveyed had actually used VR, the majority were very apprehensive. 59% were concerned that using VR could alter their sense of right or wrong. 58% were worried that VR was addictive, and 69% thought that VR would make users less aware of the real world.

However, I wouldn’t be worried about this holding back the growth of technology in any significant way. As we saw with the advent of the internet, people will always be fearful about change. This isn’t to say that the concerns above are completely unfounded, but I believe that we will find an equilibrium.

As early as the Power Boy, and Sega VR, people have reported negative side effects due to VR. Up to 1 in 4,000 people may experience a range of symptoms, such as seizures, and blackouts, even if they don’t have a history of epilepsy.

A more common side effect is VR sickness. When headsets don’t have a sufficient framerate, or lag, there’s a gap between a player’s movement and what they see. Thanks to this, between 25-40% of users may experience queasiness at some point.

There have also been fears that prolonged use of VR headsets can cause myopia. However, if the focal distance on the display is far enough away, this should be unlikely. Some of the best VR headsets, such as the Valve Index and the Vive Cosmos have much better displays and are more comfortable on the eyes, which vastly reduce the possibility of myopia and other eye disorders associated with VR.

Concerns about privacy have also been raised, since VR headsets use persistent tracking, and may be vulnerable to mass surveillance. While this may seem a little tin-foil-hatty, consider that Facebook already has placed cookie trackers to follow your data around the internet. With the huge investment they’ve sunk into the Oculus Rift, and VR development, what’s stopping them from finding a way to monetize how people use their headsets?

Currently, one of the main issues with VR becoming more mainstream is just how expensive it is. Having large, incredibly immersive set-ups like CAVEs is pricey, so most people will stick to their relatively cheaper headsets. However, with over 200 companies now competing in the VR market, we can expect to see this competition eventually driving prices down. Some futurists predict that the next step in VR is an immersive holodeck, that uses haptic feedback to let players explore interactive worlds. Unfortunately, we’ll need to restrain our excitement - we’re probably a few decades off from this kind of technology.

And how about using VR in the workplace? Is a completely virtual office in the cards? Sophia of Video Conferencing Daily has an optimistic vision of VR in the workplace. She describes employees working in individual, virtual offices, with the “digital door” left open for coworkers to come and go as needed. There might even be common areas - a digital version of the office kitchen, if you will.

There are several advantages to this kind of set-up. For example, telecommuting employees are more productive, and take less sick days. Businesses also benefit, by having reduced real-estate costs.

So, as VR becomes more widespread, can we expect to work from home in the near future?

Well, no. Although there are some fantastic benefits to telecommuting, some large firms have banned it altogether. In recent years, both Yahoo! and IBM have completely recalled their telecommuters, due to a variety of concerns. Top amongst these was the fear that employee isolation was decreasing creativity. Although the vision described earlier has some ideas to increase employee interaction, we have to ask just how practical VR would be compared with traditional methods. Although there may be workarounds to increase employee socialisation, it may be awkward to bond over video chats. At least in the office kitchen, you can share a cuppa!

Additionally, the up-front purchase of VR headsets, or smart glasses, for an entire workforce is likely to dissuade any but the richest companies. Even for companies where VR headsets can come in handy, like architect firms, the technology still isn’t appealing enough for the price for many to make the switch from their usual methods.

So, while we most of us will still have to commute to our 9-5 in the future, AR has found a niche in some workplaces.

Released after much fanfare, the Google Glass flopped spectacularly. However, Google realised that while mainstream consumers had rejected the technology, some companies had actually developed their own software to use with the smart glasses. Google decided to quietly rework the Glass for the corporate market, releasing the Google Glass Enterprise Edition in 2017.

One company that uses the Enterprise is AGCO, an American multi-billion dollar firm that builds large agricultural equipment. As most of their orders are unique, manufacturing workers had to regularly check the specifications on company laptops, that were far from their work stations. But now, the Glass has almost completely replaced their old systems. They can wake the screen as needed, and access instructions at a glance. They can even zoom in on what they’re working on, ask where certain parts go, and ask for remote assistance. Peggy Gulick, an executive at AGCO, declared that when they were first trialing the software, productivity levels increased so much, they re-tested to make sure they hadn’t made a mistake.

While the Glass Enterprise has received a warm welcome, price has again prevented widespread use. Each pair costs a minimum of $1300! However, the huge benefits that it brings close to guarantee that we will see more of this technology in the future.

VR has made great strides since its first inceptions decades ago. It has come from simple wire-frame rooms, seen through the ominous Sword of Damocles, to the ungainly consoles of the 90s, and finally a beloved part of many home gaming systems. The Oculus Rift’s success sparked a resurgence in VR technology, with hundreds of companies investing billions in this field. There are some still fearful about the impact of VR, but it is likely that these concerns will fade with time.

In any case, we are at a major turning point for VR, with widespread corporate investment never before seen in this field. It’s likely that advances will be made in room-size VR, as well as more affordable VR for the workplace. Perhaps we will even see full-on, futuristic holodecks - but only time will tell.

What do you think about the future of VR, where will it be 10 years from now? Share your thoughts with me using the comment box below.

The History and Evolution of Virtual Reality